By DAI Wentian

Translated by GU Yiwei

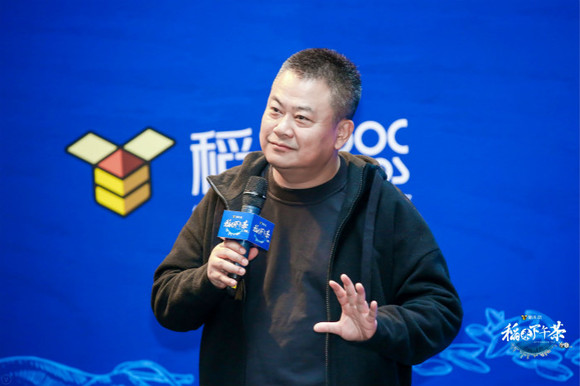

On the last Sunday night of May, the second season of Once Upon a Bite, a phenomenally successful food documentary series, aired globally on Tencent Video. CHEN Xiaoqing, the mastermind behind the show, as well as many other all-time classic food documentaries, is the indisputable icon for Chinese foodies. He sums up the new season as “food twinning,” in which food from China and from abroad, comparable in taste or origin, are often featured in parallel. “Chinese food has never existed in silo… I want to narrow the gap between food served at home and food served abroad”. He recently sat down with Jiemian News to talk about food culture, filmmaking, and the future of his industry.

For Chen, food encapsulates social, economic, and cultural progress. He says that has been the case throughout history — but even more so over the past thirty years in China. “When material abundance reaches a certain level, consumption is up, and the food culture booms accordingly,” he says.

His new season is not China-centric, however. He jokes that he wants to inspire his audience to eat around the world “with a Chinese stomach.” But as a commercial documentary producer, filmmaking is not all about cultures and ideals. There are business considerations too. For example, “only three percent of the most eye-catching content makes its way into the final cut,” he explains. There are also concerns on environment, sustainability, public health, and social impact. “I have to learn to cut up.”

Speaking of the future of food shows in general, Chen is confident that the demand will remain. “[Food] can be as interdisciplinary as you want it to be. The world is wonderfully complex...I’m confident I’ll always have food stories to tell,” he says.

JM for Jiemian News

Chen for CHEN Xiaoqing

JM: Once Upon a Bite 2 is centered around culture. How do you think people’s views on food have shifted in recent years? And how is it related to cultural changes?

Chen: That’s a very broad topic. Let’s take sugar for example. Sugar, which is featured in our first episode, has been the symbol of wealth for the most part of human history. Only the rich had access to sugar. Kids call candies “treats” on Halloween. In Britain, sugar in afternoon tea used to symbolize “middle-class status.” But today, it has become something to fear. Whether you call it self-restraint or even self-knowledge, we are actually very conflicted. Our genes make us easily addicted to sugar, but our rationality tells us to refrain from it.

Another example is organ meat, which was an everyday food until half a century ago but is abhorred by people today. Even in America, bone marrow and pig intestines were quite common in home cooking during the Great Depression, per The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals by Michael Pollan. People began to shun organ meat mostly after World War II, when offals started to be discarded or used for non-food products in large-scale, industrial meat processing.

JM: Such changes must have also happened in China in the past 30 years, given all the social and economic developments?

Chen: Correct. The food scene was a bare minimum thirty years ago. Unlike today when everyone prides him or herself for being a “foodie,” food obsession was shameful even in the early nineties. I myself first heard the word “gourmet” in 1987 during a “China Food Festival,” where I worked on the camera crew. Back then the common thought was that the fancy food featured there was for foreign visitors, and frugality was a virtue that we, Chinese, should stick to. But look at it now! When material abundance reaches a certain level, consumption is up, and the food culture booms accordingly.

Today people define “gourmet” food in different ways. Some are rather out of touch with our daily lives. Some people worship empirical court cuisine: only the old, aristocratic are good. Some have adopted the western, haute cuisine approach to food. Even a run to the downstairs hole-in-the-wall restaurant has to be a ritual.

Granted, historically, taste is defined by the rich and the powerful. But the joy of food is far more democratic. My years of work has connected me with many food critics, historians, and anthropologists, who have confirmed my belief that the average person can derive as much enjoyment from his weeknight dinner as a king or billionaire from a feast.

JM: There are actually many simple, quotidian foods featured in the new season of Once Upon a Bite.

Chen: Right. And, we’ve refused to use “derogatory” words to describe the food or its provenance, such as barren, remote, bare. Food is just food. No judgement.

JM: It has become the mainstream for food shows to be centered around culture. Do you think one day food documentaries will run out of stories? How will this genre evolve?

Chen: I’ve been asking myself the same question actually. There are infinite stories to tell about human life and human society, even from the perspective of food. But I’m a media worker, not a researcher. Whether and how far I proceed in this direction depends on market reception. Essentially, if the viewers are not interested, or are bored with it, I’ll have to call a halt and find another approach. It’s strictly business.

Even compared to our peers globally, our team already has top notch shooting and editing capability. With these, can we explore different themes and structures? This is something I keep asking myself too.

JM: What are some major differences between food documentaries produced by Chinese filmmakers and their global peers, in terms of themes and structures?

Chen: The difference mainly lies in the story, or, “moral of the story”. That affects the arguments as well as the structures. We used to shape our subjects into a form and rhetoric that’s familiar to the western audience. Now I strive for a storyline that’s compatible to as many cultures as possible. Sometimes I feel that for western filmmakers, their themes, materials used, and even methodologies are bound by existing stereotypes and myths. And when I point it out to them, many would say “that makes a lot of sense. I’ve never thought this way before.” It’s not just filmmakers. Many renowned food researchers also don’t realize these stereotypes.

JM: What are some common stereotypes?

Chen: A common myth is that Chinese food is all about “eating with a big family”. So any story about Chinese food is centered around this theme. But Chinese food is evolving and becoming more diverse. For example, many nuclear families don’t cook a spread of food every day. Continental style dining, in which dishes are portioned and served individually, is increasingly adopted even at homes. Historically, before the Song Dynasty (about the 11th century), dishes were more often splitted than shared. This can be surprising to many western filmmakers, for whom every Chinese food story is a “sharing with friend and family” story.

JM: What about flavors? Are they perceived differently?

Chen: One man’s meat is another man’s poison. Many tastes savored by us can be off-putting to a foreign consumer. The same can be said for our vocabulary for food and flavors. These differences are rooted in our history and culture. Another thing I’ve noticed, is that in many countries people tend to have more unanimous views on cooking, food, and taste. In China, we can be very divided in how to make and eat a dish - some recipes and tastes are just “more right” than others.

Of course foreigners can also have strong opinions about what’s “legitimate.” For example, once I mentioned Fuchsia Dunlop to an expat of a German company. He has a lot of respect for Fuchsia’s knowledge of China, but was unconvinced of her status as the most knowledgeable Westerner about Chinese food. He jokingly asked “Are you sure? How can a Brit know anything about food? And Chinese food?” What we can see here is that everyone has his/her own value judgement on “legitimacy” and “authority”.

JM: There is a lot of discussion about foreign dishes in the second season of Once Upon a Bite, many of which are told in parallel to a comparable Chinese food. But how do you convey an unfamiliar taste to the audience through sound and image? For example, there was an episode that mentioned baklava, which few Chinese viewers have tasted before. How did you explain what baklava tastes like on screen?

Chen: That’s a challenge, to be honest. We know foreign food feels distant and irrelevant to the audience. In the first season, foreign food content only received got a third of live comments per minute compared to Chinese food.

But that’s the point of us making the show in the form of “food twinning.” We want people to know that Chinese food has never existed in a silo. There are so many similarities in ingredients and cooking methods across different food cultures. Karasumi, traditionally eaten in Taiwan and Japan, is essentially the same thing as bottarga in Italy. Jinhua ham, Iberia ham, and prosciutto di Parma all appeared around the same time a thousand years ago. Yes it’s a lovely coincidence. We Chinese want to showcase our culture, including food culture, on the world stage. To do that, we need to first understand what people in other countries eat and how they live.

In addition, I also want to narrow the gap between food — at home and abroad. Food is an intrinsic part of life. So how do we convey not just the taste, but also the emotions and historical significance associated with it? Is there a Chinese counterpart? Take the Turkish baklava as an example. We featured it together with yougao, a layered pastry from Yangzhou, another transit and trading hub on the other side of the continent opposite to Istanbul. Both were luxury items in ancient times when sugar was a scarce commodity. Both symbolize “slow food” and a refined lifestyle in their respective traditions. When it comes to photography, we zoomed in on the intricate foldings of sugar and laminated dough in both pastries. We want to speak to the audience’s via all of their senses.

To put it another way, a Chinese stomach can enjoy food around the world.

JM: You mentioned just now that the “food” part of the documentary feels sensual, but the “cultural” part of it can mostly be elaborated only through narration. How do you balance the two?

Chen: We have refrained from excessive use of “cultural lecturing.” After all, Once Upon a Bite is a commercial documentary, so the priority is to use plots and images to reconstruct a sense-of-presence experience, i.e. to show the food is great so that people are willing to watch. A documentary filmmaker needs to do 100% of the homework, if not more, but only three percent of the most eye-catching content makes its way into the final cut.

Of course it’s agonizing to participate in the edit. I once did a story on pickled garlic, a very popular relish in northern China. The science of it is fascinating, at least to me. There are particular requirements for the temperature, the acidity, etc. But if the episode about pickled garlic spends ten minutes showing how the garlic cloves are transformed in the brine in slow motion, people will simply switch channels. So, only three sentences on the science. I have to learn to give up.

JM: Speaking of giving up, you once mentioned that you had to give up shooting coconut crabs out of environmental and sustainability considerations. Are there many other similar cases? What are your criteria for giving up a story?

Chen: Oh, so many! Some stories are killed even after the shoot is done. Endangered species, like coconut crabs, are taken out straightaway. Can’t eat them, right? Unhealthy food, such as carcinogenic food, no matter how popular it is or used to be, has to be killed. I myself may still eat some of them occasionally, such as the herb fish mint, but it’s a different matter showing it to thousands of people. As a media worker, I have to think about the public health ramifications. There are also concerns on social and moral impacts. Some food is morally acceptable for a small group of people, like animals that potentially can also serve as pets. If it’s too controversial, we won’t touch it.

JM: As you said, to make commercial documentaries that reach a wide audience, you have to think through every aspect of it and expect all potential ramifications.

Chen: Exactly. A good example is David Chang’s Ugly Delicious. Eye catching as the title is, every single character in it is treated with dignity and respect - which I think is the golden rule for documentary makers. But you’re right, no matter how bold or unconventional the title or form is, when it comes to content, commercial documentaries are conservative. Every filmmaker is extremely careful.

JM: An increasing number of food shows are coming to the market. Do you think the market for the genre is saturated? Many themes, other than culture, can be related to food. Do you have plans to explore any of them in your future work?

Chen: I disagree. I don’t think there are too many food documentaries these days — since there is still unmet demand. Data shows that food programming viewership is growing fast around the world. So the demand is there.

I sometimes read reviews for Once Upon a Bite. Some people call it a “reality TV show.” I’m not upset at all - documentaries are nothing sacred. If the viewers enjoy my food stories, and can derive even a little bit of reminiscence, reflections, or just enjoyment from them, I consider it a mission accomplished.

Also, as we discussed before, nowadays food shows are centered around culture. But it doesn’t have to be. The scope is so large. It can be related to ethnicity, faith, or science. Think about it, there’s geography, botany, zoology, and all sorts of disciplines in it. It can be as interdisciplinary as you want it to be. The world is wonderfully complex. Even if the “market” for food shows shrinks at some point, I’m confident I’ll always have food stories to tell.